In the 1960s, computers were still massive and unwieldy machines, performing tasks for large organizations, such as processing checks and calculating ballistic trajectories. People had to submit punch cards to system administrators, who would input them into the computers. Then they would wait for the computers to process the calculations and print out the results. This was the typical batch-processing approach.

In 1946, while serving as a naval radar technician in the Philippines, Doug Engelbart came across Vannevar Bush’s famous article “As We May Think.” This visionary and influential article predicted many aspects of the information society.

The article had a profound impact on Engelbart. Gradually, he began to think that computers should not just be used for calculations. In daily work, people often need to look up information, draw charts, and edit documents. Computers should play a significant role in these tasks, helping people work more efficiently and enhancing human intelligence. Isn’t that a great idea?

However, at that time, his peers thought it was heretical and constantly attacked him: “Computer time is more valuable than human time. This won’t work. It’s just a pipe dream.” “Interacting with computers is a waste of time. The truly valuable thing is artificial intelligence…”

You see, real innovation is very difficult. What seems commonplace today was fiercely opposed back then!

In 1962, the undeterred Engelbart wrote a report titled “Augmenting Human Intellect” and began frantically seeking “investors.” He faced numerous rejections. Even the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, which had previously given him a small amount of funding, began to doubt him. His colleagues and friends also thought he was no different from a charlatan. At this point, even Engelbart himself felt like he was on the brink of failure. But what he didn’t know was that his benefactor was about to appear.

Earlier, we set the stage to make it seem like the idea of “human-computer interaction” was unique to Engelbart, but that’s not the case. In 1960, a man named Licklider wrote a paper called “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” predicting interactive computing. More importantly, Licklider held a very significant position: he was the director of the Information Processing Techniques Office at DARPA.

DARPA was established by the United States in response to the threat from the Soviet Union. This organization supports high-risk research without much red tape and bureaucratic procedures, and it has given birth to many results that have impacted humanity. The most well-known is the Internet, which we will talk about next time.

Licklider had a friend named Bob Taylor, who also believed in human-computer symbiosis. At that time, Taylor was working at NASA. When he saw Engelbart’s report, he was immediately struck by it: Wow, someone is actually trying to implement Licklider’s human-computer symbiosis, and the description is so clear. I must invest in him!

Taylor immediately contacted Engelbart to meet in Washington, D.C., on the East Coast, and brought Licklider from ARPA along. They gave Engelbart a substantial amount of money.

With the backing of NASA and ARPA, Engelbart could now fully realize his vision. He established the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at Stanford University to develop a revolutionary online computer system called NLS (the oN-Line System). The goal of this system was to enable human-computer interaction, a groundbreaking concept with no prior experience to draw upon. It was like a blank canvas waiting for Engelbart’s team to create something new.

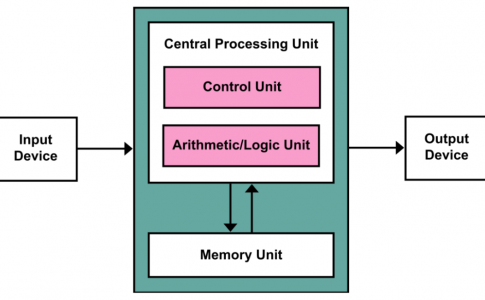

At that time, there were no hardware or software available. Everything had to be built from scratch. For example, since computers did not have display devices, how could they show real-time interactive interfaces to users? They had to build one themselves, which cost $90,000.

Once they had the interface, how could users select and operate on it? How could they edit and navigate through documents? How could multiple people collaborate? There were many such questions, and Engelbart’s team worked tirelessly for six years to develop the NLS system.

In 1968, ACM and IEEE were holding a joint conference in San Francisco. Taylor strongly encouraged Engelbart to attend and showcase their work. He believed that a public demonstration was necessary to truly convey the significance of their efforts and to change people’s preconceived notions about computers.

How could they create an impressive demonstration? We might think of Steve Jobs and his Apple product launches, where he often demonstrated the products in real-time, with the audience seeing both Jobs and the device he was operating on a large screen. This kind of real-time demonstration is the most effective.

Over 50 years ago, Engelbart had already thought of such a demonstration, but there were no similar devices available on the market. They had to custom-build a set of equipment. This included four cameras to capture video from four different channels: Engelbart’s face on stage, the computer he was operating, and two computers at Stanford University campus 30 miles away. They also rented a microwave link to transmit the video signals and built a 2,400-baud modem to transmit computer instructions over rented telephone lines. Finally, they needed a device to mix the four video signals and project them onto a screen on stage.

This custom equipment cost $175,000 in 1968, equivalent to one million dollars today! However, the wise Taylor reassured Engelbart, “Listen, spend as much as you need, but don’t skimp—have enough redundancy so that things will really work. Don’t worry. ARPA will cover the cost.”

On December 9, 1968, at 3:45 p.m., in Brooks Hall in San Francisco, Engelbart sat nervously in front of a computer, facing an audience of 2,000 professionals, and began his presentation:

“We’re all in research, so imagine if you had a computer in your office, running all the time, always on standby…”

He paused here, smiled at the audience, and continued, “In other words, it would respond to human instructions. Can you imagine the value this technology could bring?”

He then began to demonstrate the groundbreaking technologies:

-

The Mouse: The device on the right in the image is an incredibly great invention that we can’t live without today. The mouse is primarily used for convenient and flexible positioning on the screen.

-

Graphical User Interface (GUI): Completely abandoning punch cards, users could operate through a series of overlapping windows. Over a decade later, GUI was widely commercialized by Apple computers, and more than 30 years later, Windows popularized GUI worldwide.

-

Word Processing: Users could create documents, insert, delete, copy, and paste text. This was the prototype of modern word processing software, which would only become popular on PCs over a decade later with software like Word.

-

Hypertext: Through “hypertext” links, users could quickly jump between related documents. In the 1990s, Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the Web popularized hypertext.

-

Online Collaboration: NLS supported network collaboration, allowing multiple people to work on a single document simultaneously when multiple NLS systems were connected. This was at least 30 years ahead of Google Docs’ text collaboration.

-

Video Conferencing: This technology, which seems rudimentary and crude today, was truly revolutionary in 1968. If you put yourself in that context, you would see the brilliance of the technology behind the demonstration, illuminating the path for computer development over the next few decades. These revolutionary interactive technologies all appeared at once, leaving people in awe: Computers could be used for so much more than just calculations!

Alan Kay, who was in the audience and later invented Smalltalk and the concept of object-oriented programming, described the experience as watching Moses part the Red Sea. Engelbart showed them a highly promising new continent and guided them through the rivers and oceans they needed to cross to get there.

When the stage lights dimmed, Engelbart stood up from his console, relieved. The other computer scientists in the audience “stood, clapping and cheering wildly.” Engelbart had glimpsed the future and created the computers we are familiar with today. This demonstration would later be known as the “Mother of All Demos.”

In the early 1970s, members of Engelbart’s team gradually left the Augmentation Research Center to pursue their own paths. Many of them eventually joined Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), which would become the next hub of innovation. In 1973, PARC introduced the Alto personal computer, which was similar to NLS but smaller and more refined.

Alan Kay, who had been in the audience during Engelbart’s demonstration, designed a programming environment called Smalltalk on the Alto, introducing the concept of object-oriented programming. With its mouse-driven GUI, Alto caught the attention of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, ultimately leading to the creation of Macintosh and Windows and sparking the personal computer revolution.

The seeds planted by Bob Taylor and Engelbart in 1962, through NLS, Alto, Macintosh, Windows, and the Internet, finally bore fruit in the industry. Over 50 years later, we still live in the world that Engelbart built, with these technologies as ubiquitous as air and water.

No comments